|

In our last post, we talked about what happens when a closely knit, core group of students take ownership of their learning. Putting on new habits is not easy for transfer students who tend to get through oral lessons, readings, worksheets, and then mentally checking out until the next demand. It takes time to adjust to more open-ended ways of doing things: choosing passages for copywork, narrating what interests them in a reading, adding to a conversation about a reading, deciding what to notebook after a nature walk or for a book of centuries entry, etc. They are not used to having so much responsibility -- every day they clean their cubbies, do chores, and set the example for the primary classes at morning meeting. Imagine the first half hour of the first day of school for an transfering elementary student. Primary and elementary classes gather in the big room for the morning meeting for an abbreviated "morning time." We sing a song (hymn, praise, folk, patriotic, or holiday) followed by the pledge of allegiance. A teacher reads a psalm (not a devotional) and hands fly up. A fourth grader asks what a word means. A sixth grader notices that the psalm talks about something that reminds them of David or Jesus. Even first and second graders have something to say about a psalm! After that, the elementary class heads to fifteen minutes of Spanish. A lot of short lessons are packed into that half hour. The rest of the morning offers language arts lessons and lots of narration. The class writes a narration of a chapter from a book they read the night before for homework -- without talking about it, without questions to jog their memory, without even looking at a book. They have a blank piece of paper, and that is it! The same is true for oral narration -- after a reading, books are closed. One student retells, another student picks up the thread, and it continues. All the while the experienced students add on things that have not been mentioned. Along the way they generate their own questions, make their own connections, and come up with ways to explore the ideas further. The teacher monitors the process and offers guidance as needed. At first a new student struggles. Learning to pay attention to a ten- to fifteen-minute reading well enough to retell the material is hard! We often hear "Oh, I know!" followed by, "Never mind. It flew out of my head." First narrations are halting, and words are jumbled, and names and places are forgotten or confused. New students are challenged by memorizing poems and Bible verses and they have no idea what book to use for copywork, and studied dictation addresses grammar, punctuation, capitalization, as well as spelling. Life without worksheets sounds great until faced with a blank page and wondering what to draw or write. Students are broken up into many small groups for individualized math instruction and sometimes "build" their own worksheet by using dice to come up with numbers for problems. Some are actually excited about math. Math? One day we focus on paper sloyd and the newbie wonders why the teacher demands exact measurements. Then a more experienced student walks over with a tray that he made while novices were still learning how to draw diagonals correctly. He leans over and says, "Ms. Tammy may be picky but you'll thank her later." Then suddenly someone asks for permission to make an announcement and says, "I would like everyone to know that I have been working hard on a percent problem and I finally, finally, finally understand it." She does the Rocky stance, and everyone claps. Thursday after lunch launches the end of the school week which is noticeably different. Elementary and above meet in the big room to do Shakespeare's Macbeth. They break up into small groups to practice a five-minute scene and meet in the big room for one group to act it out. Some kids are total hams and come up with all kinds of improv. Some are shy and simply read their lines. Even fourth graders get to read lines and most love it because they still remember how to play and play is the thing!

0 Comments

We have been eagerly watching our elementary class this year. For the first three years of Harvest's history, learning together melded them into a tight-knit group. Every day they live the habits instilled by a Charlotte Mason education -- curiosity, imagination, initiative, effort, and discipline to name a few. Here is a peek into that class's history discussion of the beginnings of the Carolina colonies to show you how owning their learning looks: The class was wrapping up a narration about South Carolina's transition from being a proprietary colony to a crown colony, its split from North Carolina, the movement of its capitol, and the finalization of the border which happened only recently. Suddenly, one says, "Wait a minute! I want to go back to Columbus. Didn't someone else come to America first?" The students begin to have a "grand conversation" and their teacher stepped aside and listened. "Don't you remember we read about Leif the Lucky?" "Yeah, it was a colorful book that looked like cartoon drawings!" "I was in Ms. Tracy's class. I read about it in a different book." "I don't remember reading about him at all." "Wait. Who remembers reading it? [Discussion of who remembers reading it.] Okay, maybe we read it the first year because C and G came the second year and they don't remember reading it." "Ms. Tammy, can you give me something to read about him? I want to know more."

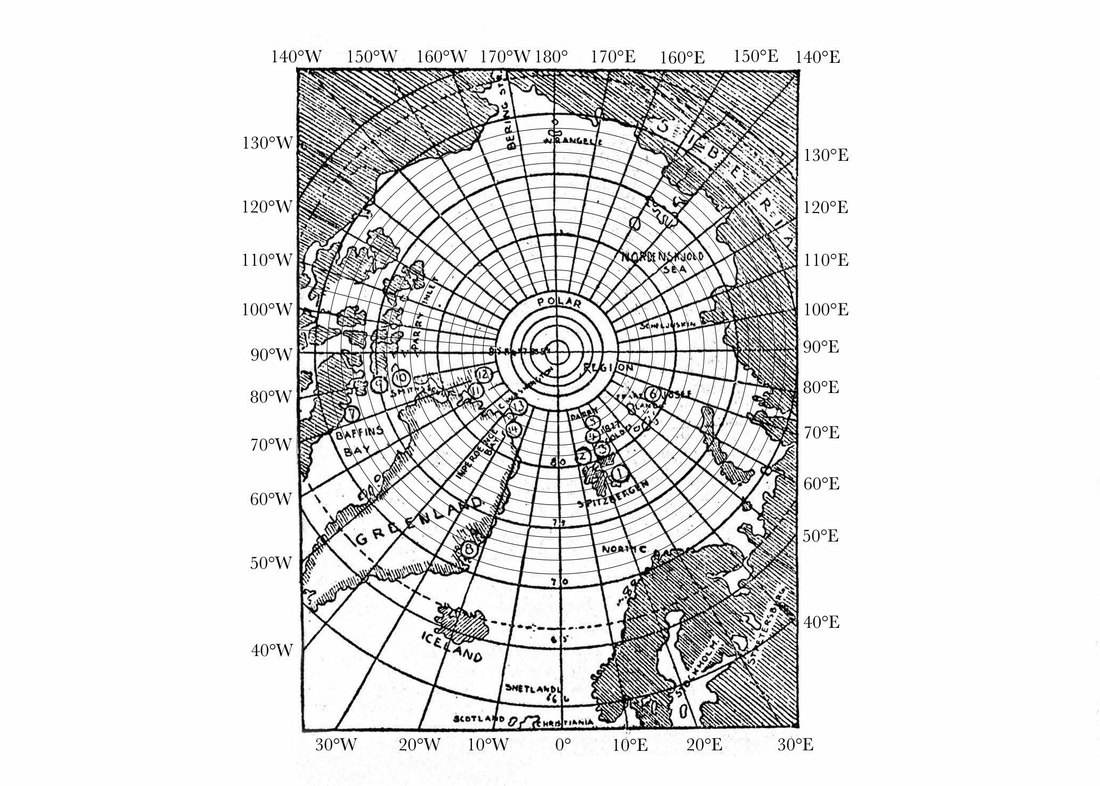

One student asked, "Do you think it would be a good idea to make an index of symbols so I can make a symbol to show this was the year he died?" I answered in the affirmative and said that people today who make bullet journals do that very thing! Before Christmas, another grand conversation following a history reading led us into a geography lesson which tied into science as well. We had been reading about the first border of Carolina which went from 30˚N to 36˚N latitude from sea to sea. "Sea to sea? Are you kidding?" The next day, I brought copies of the first map of America so they could see how understanding of this continent has changed over time. They were shocked that North America looked like a long, thin island. Another student pondering the idea of North asked, "I get latitutde and longitude mixed up. Can we go over that?" I grabbed the nearby globe and we did a quick review of terms like globe, equator, hemisphere, poles, and latitude. Striking while the iron was hot, the next day, we did a map study of a blank outline map to see which borders fell along lines of latitude. That lead to a conversation about some states having borders with rivers. We did the same thing for longitude and then I made a sheet with a map for them to practice locating a point by latitude and longitude as well as figuring out and writing down coordinates. Typically what happens is that the map lovers finish early and then help the students who need extra help because having to teach an idea to a peer strengthens their understanding. In the middle of exploring latitude and longitude, another student asked, "I have heard the term magnetic north. How is that different?" This student's curiosity was perfectly timed for several reasons. One of our science books is about the Peary expeditions to the north pole. With Christmas looming on the horizon, even the youngest students in the class were interested in learning about the arctic. I asked the class questions to assess their knowledge and they had a basic understanding of the north pole and how there is not a real pole. It is an imaginary axis that we draw through the earth to help us understand its tilt. Then the history lesson that morphed into a geography lesson was now morphing into a science lesson. Falling back on navigation classes when I was in the Navy, I warned them that working with true north is going to stretch their brains because the best kind of maps for that region of the earth are called polar maps which are round. The map lover in the class echoed, "Round? What do you mean?" I walked around with the globe to show them how the lines of latitude look like circles if you are looking at the perspective of the north pole as the center of the map. I explained that the earth is like a big magnet and magnets have two poles. Suddenly, one says, "Wait! So that is why we call it the north and south poles?" "Yes. The inside of the earth is metal, especially iron. That metal becomes magnetized. Magnetic north and south do not stay in the same spot. In fact, sometimes, the poles suddenly reverse or move far away from the poles. Morevover -- now this is going to blow your mind -- the location of magnetic north and south changes slightly from day to day. When I was in the Navy, we had to correct for magnetic deviation because it affects the reading of a compass. I have an idea! This may be hard but I think I can make a map and you can plot the changes in magnetic north for the past a hundred years." I spent part of a weekend looking up the coordinates and preparing a polar map in such a way that would scaffold their ability to plot on one. I labeled the lines of longitude along the border and added more latitude rings. The morning of the day we were going to make our plots, one student confided to his mother, "I'm so excited! We get to plot magnetic north today." Again, some students caught on more quickly and, when finished, they helped the ones who were struggling. The class was amazed at how much magnetic north had moved over a hundred years. One said, "Can we do more polar maps after Christmas?" I answered, "Yes. It might be fun to plot Peary's travels in the arctic." A final example of how owning their learning looks happened over Christmas vacation. One family was traveling to Colorado to ski. Since I lived there for two years and I know this young man loves nature, I told him that he needed to look for three things: mule deer, abert squirrels, and ponderosa pines. When he returned, he excitedly told me about their trip to the Dinosaur Museum, brought out his fish fossil, and showed me a picture of a dead mule deer on the side of the road and a ponderosa pine. He gave me a cluster of pine needles! I asked him if he had done any nature notebook entries and he had! When the time came for Spanish, I notice he did not have his Spanish notebook. He explained sheepishly, "I left it in my bookbag. and it's in Colorado. I was so excited to see family that we hardly ever see. I brought my notebooks because I wanted to show them what I've been learning in school." I will close with a few quotes from Charlotte Mason that go along with students who own their learning: "TEACHERS SHALL TEACH LESS AND SCHOLARS SHALL LEARN MORE." |

HCSA community called to offer another way to learn for students in Clarendon County Archives

December 2019

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed